Polybius

By Hannah Ibbotson

The motivation of the victors masks the voices of the imprisoned. These words ring true for one Greek historian named Polybius. Polybius was a member of a political group within Greece who was one of the last few people attempting to push back the power of the Roman Republic. Though taken prisoner, he was allowed to travel around with generals and attend political meetings. This freedom not only allowed him to move around the known world but see historical events first hand. His literary freedom was less, though. His most famous written work, Histories, would be published under the watchful eyes of Roman rulers. Polybius’s circumstances forced him to write about, if not view, Rome favorably while developing theories to explain their superiority within the Mediterranean. (Eckstein, 10)

The Rise of a Historian

Polybius (c. 208-125 BCE) was a Greco-Roman philosopher. Born around 208 BCE in Megalopolis, Arcadia, within the Achaean League, a federation of city-states within the remaining Greek land, which was allied with Rome until their dissolution in 146 BCE. This League was fighting against the Antigonid Macedon, who was ruled under a tyrant king. Polybius’s father, Lycortas, however, brought the attention of Romans when he began expressing anti-Roman rule beliefs. Lycortas believed that the Achaean League was the last Greek power that would have been able to stop the expansion of Rome into the ancient land.

Philopoemen, the leader of the Achaean League, wanted Rome to acknowledge the Achaean League was an equal power within the Mediterranean and through his policies was able to keep out the looming republic up until his death. This brought the Roman empire over to Greece, and thus 1000 members of the League were taken as hostages in 146 BC with Polybius being among those chosen. Polybius was taken in by Publius Cornelius Scipio, a Consul within the Roman Republic. As such, Polybius was allowed to move around relatively freely in his captive state, leading him to learn about Roman history as well as travel with his master during the Punic Wars in which is book Histories is about. Though Polybius wasn’t able to express his negative views on Rome, his book was used to explain the expansion of Roman control over the Mediterranean as the republic gain control of vast amounts of land as the result of the Punic Wars.

From Greece to Rome

The Greek Hellenistic period could be characterized as the time between Alexander the Great and the conquering of the Greek City-States by Rome. It was also during this time that outside thinkers saw Rome as the new world leader as in the 53 years between 220 BC and 167 BC, they were the only nation known to have conquered the entire world which had been identified at this point. This rising power was in stark contrast to Greece’s main rivals of the Persians and the Spartans, who had tried for centuries to conquer the known world without luck. It was this power that lead to Polybius developing an explanation for Romes power and the reason behind their success while all others failed.

The Histories

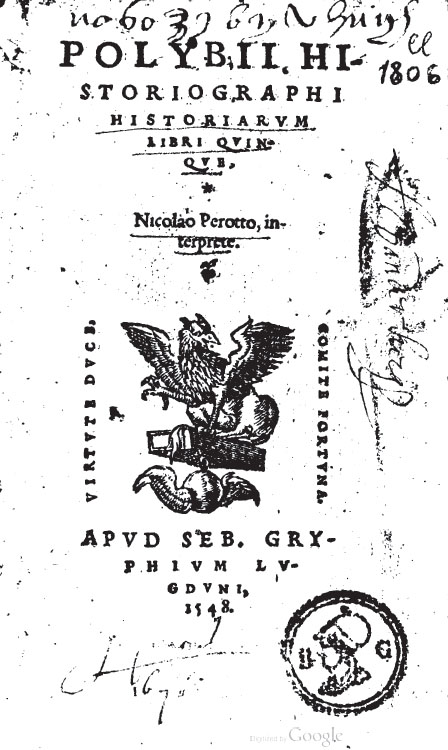

While Polybius was a captive in Rome, he wrote his Histories, which encompassed the history of Rome from 264 BC to 146 BC with a primary focus on the Punic Wars along with commentary on the historical profession and methods. Due to his unique circumstances, he was allowed to travel around with Scipio and gain first-hand experience and eyewitnesses of the Sacking of Carthage and other battles.

As far as historiography is concerned, the 7th book of the Histories is the most important one out of the entire collection as it is the book that encompasses Polybius’s historical methodlogy the most. His main ideas contain source analysis, universal history, cycle theory of Rome, and factual integrity of historical writing. These new historical methods were different from previous methods as history was nationally focused from third party knowledge. Though it is essential to understand that during the time of writing, Polybius was still a captive of Rome, and some of these ideas, such as the cycles of Rome as well as the history that is written, might be heavily biased towards Roman readers. He then also plays upon his experiences of Roman power to justify his advocation of universal history as this type of historiographical work could not have been possible if their known wold hadn’t been unified under one authority.

Rome: The Champion of the Cycle

With Rome rising on top as the main power of the Mediterranian, many philosophers tried to explain their success and how others failed. The concept of a cycliclar thought through political means had not been a new concept by the time Polybius stepped forward with his versions of it. Though their other historians only stuck to a three-part cycle, Polybius instead expanded on other ideas leading to his six-part cycle. These cycles were social, political while also following a biological period in which a civilization went through the cycles of birth, flowing, degeneration, death, and renewal. However, Polybius’s ideas there unique as each part of the period had both a pristine and corrupt version. He believes that every city-state experience the cycle in which one state begins eventually becomes corrupt, and then is over the throne by the next one. His sequence goes as follows: Monarchy, Tyranny, Aristocracy, Oligarchy, Democracy, Ochlocracy(Polybius, 6.4). It is then that Monarchy takes over control once again, and then the cycle starts itself over again. Polybius does not explain this cycle within his book but instead instists that “No clearer proof of the truth of what I say could be obtained than by a careful observation of the natural origin, genesis, and decadence of these several forms of government.” (Polybius 6.4) Though Polybius himself said that is was nearly impossible that any city-state was able to get out of this trend, Rome was able to do it.

The Champion of Cycles

Many Hellenistic philosophers played with the idea of a natural cyclical tend the encompassed the Mediterranean powers allowing them to explain the rise and fall of empires throughout history. Yet it was Polybius who suggested that Rome had managed to get knocked out of the cycle and become the supreme power of the time. Polybius attributes this success to two main characteristics; their political and military achievements. From the military results, he believed that by conquering other city-states in various stages of the cycle, they were able to find the faults and strengths within each political system and adapt accordingly. Polybius attributes most of Romes success to their unique form of government and their constitution. Polybius explains that the Roman Republic’s political system was a combination of Monarchic, Aristocratic, and democratic and that it was this mixed political system that saved them from the fate of the political cycle. Other philosophers came to this same conclusion during Polybius’s lifetime; however, he believed that is because of the juridical capabilities within this political system and not the mixture of the system itself. This mixed political system was another way that Rome was seen as superior in Polybius’s eyes.

Who Gets to Write History

Through the Histories, Polybius voices his opinion on who he believes should be writing about history as well as how it should be written for later audiences. He believes that anyone who writes history should have political education and first-hand experience about the topic. His opinion corresponds with the type of writings of the period, which was heavily militarized. Thus the reasons for political education. He also believes that history should be just the facts which would then come from one’s personal experience or eyewitnesses though this essay goes into further details about this later. Polybius, during his reviews of other historians, often criticize them for lack of political and military knowledge.

“the soundest education and training for a life of active politics is the study of history, and that the most vivid, indeed only, teacher of how to bear the vicissitudes of fortune bravely is the recollection of other people’s calami-ties.” ( Aristotle 1.1252a, McGing, 209)

This opinion corresponds to the rising belief of this time about the benefits of pragmatic history. Through the collective works at the time, a simple definition would entail the telling of the tale through political and military events as praxeis meant deeds. This mode of writing would make sense as the audience for these works would be reserved for privileged and powerful citizens who were often ended up within political or military roles.

Universal History

With Rome now conquering every power it can reach, Polybius suggested that it was now possible to write a universal history. He expresses his view by saying “anyone who thinks that they can understand the whole of history by reading monographs on individual subjects is like the person who thinks he can appreciate the beauty and grace of a live animal from looking at the different parts of its dissected corpse” (Polybius 1.4, McGing, 155). He believed that partial history or case studies did not contribute at all to the learning of history as these did not help to explain the rest of the world further.

It is only by the interweaving and comparison of all the parts with each other that noting their resemblances and differences, we reach a stage where we are able to do a general review and thus derive both benefit and pleasure from history.” McGing, 156

Throughout the Histories, Polybius expresses his hatred for monographs, the detailed study of a single subject or event. This is because he believes that the historian would never be able to understand the world as a whole through these means. Through these universal histories, he explained political entities, events, and the geography and used this to explain how actions within one city-state would affect others (McGin, 156). This new theory of history might have been thought about as Greek City-states were declining under the power of Rome as they were spreading their influence across the world. It was through his work of universal histories that he hoped to achieve a way to explain how the land was conquered by the Romans by describing the events that lead to the weakening of the city-state.

“In earlier times the world’s history had consisted, so to speak, of a series of unrelated episodes, the origins and results of each being as widely separated as their localities, but from this point [the 140th Olympiad: 220–216 BC] onwards, history becomes an organic whole [somatoeides]: the affairs of Italy and Africa are connected with [inter-linked with – symplekesthai] those of Asia and Greece, and all events bear a relationship and contribute to a single end.” Eckstein, 330

Bibliography

Eckstein, Arthur M. “Polybius, Phylarchus, and Historiographical Criticism.” Classical Philology 108, no. 4 (October 1, 2013): 314–38.

Ingls, David, and Roland Robertson. “From Republican Virtue to Global Imaginary: Changing Visions of the Historian Polybius.” The University of Chicago Press 108, no. 4 (October 2013): 314–38.

Lemon, M. C. Philosophy of History: A Guide for Students. Routledge, 2003.

McGing, B. C. Polybius’ Histories. Oxford Approaches to Classical Literature. Oxford University Press, 2010. http://libproxy.unm.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat06111a&AN=unm.EBC497620&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Popkin, Jeremy D. “What Is Historiography?” In From Herodotus to H-Net : The Story of Historiography. New York ; Oxford : Oxford University Press, [2016], 2016.